Folly of Desire – Program Note

Tacit Consent

Lovers give themselves in a moment of trust – or they dare to take without asking. The fact that this giving and taking is without an established contract – there is risk – is what gives desire its wings, and also makes it potentially transgressive. Consent exists ideally, but it is unspoken. This tacit quality of consent makes it downright holy for poets, artists and musicians – quiet, untouched by all the prosaic discourse. Desire – unrequited, or consecrated in ecstasy – is a strong trope in music, wrapped into the game of tonality itself: tension and resolution, tension again, and resolution. In its unspoken abstraction, music can trace lucidly an intimate exchange.

In the initial idea for this song cycle, the order of the songs was to reflect a spiritual climb from pure lust all the way to lust-free love. That ascension, though, would import a moral message into the music: that carnal desire itself was base and ignoble, and love free of desire was the highest achievement. It was too simple. Music should provoke more questions, not answer them with prescriptive finality.

The next thought was to address lust only and thus confront it directly and unapologetically. Too unapologetically, though – might that serve to celebrate what one would condemn? Finally the goal was to neither condemn nor sanction, yet still probe the subject without dodging “should” and “shouldn’t” questions.

A discourse about what may and may not take place, and an attempt to find a provisional consensus, is valuable. It might focus on just how one defines consent. There should remain, though, a private space where one can just love someone and take without asking.

This privacy has been a cherished freedom of liberal societies, but is under question now. When sex enters the public forum, it becomes political, and we speak of a citizen’s right to privacy. Closely related is freedom of speech. Sexual expression, like speech, often takes place in a relatively anarchic locus in which there are no fixed rules and no policing presence nearby. If someone is asocial – forcing an unwelcome sexual advance, or inciting violence through speech – the governing body is compelled to paternalistically step in, halting the expression. Some children are misbehaving, so the whole classroom will suffer.

This point in history is unique because leaders are doing the opposite: they are goading the anti-social expression onward. A vote, as an expression of speech, has become a raised middle-finger, a malevolent gesture. The free-roaming playful kind of anarchy is threatened from the inside.

Romantic Irony as Self-Censure

Heinrich Heine’s title for the collection of poems that Schumann drew from was Buch der Leider – Book of Songs – proclaiming the quality of song already in the poems. When Schumann titled his song cycle Dichterliebe – the “poet’s love” – he effectively returned the authority to the first-person protagonist of the poems. Authority over

himself is the struggle of this passionate figure, who is always in danger of drowning in his rapture for a young woman, losing his common sense. Schumann conveyed masterfully that unhinged mental state in his musical expression: at turns violent, euphoric, dreamy and unreal.

Heine’s Romantic irony, as it came to be known, involved an act of self-censure from the poet, in which he would assess the folly of his own ardent feeling within the same poem. It might be a painfully jarring corrective, yet is less destructive than the folly of losing his wits completely, obsessively pining for someone he will never possess.

Heine’s caustic reawakening to reality is particularly effective in Schumann’s musical dramaturgy when it is deferred until the end of the poem, as in IV, “Wenn ich in deine Augen seh’” and VII, “Ich grolle nicht”.

In those two settings, Schumann’s gambit is not to change the musical fabric at all – making the abrupt mood change of the text even more tragically apparent by understating it. It’s a real German Romantic move – wearing the emotion on your sleeve and holding it in at the same time, verklemmt. That kind of narrative dissonance also foreshadowed modern cinematic intentional incongruity – like when Scorsese sets a violent scene to cheerful doo-wop music.

The perpetrators in the #MeToo accounts and the Catholic church sanctioned their actions through willful fantasy, essentially lying to themselves, not unlike the 19th Century personage in Dichterliebe. A measure of Heinelike self-critical distance might have helped them avoid a destructive path. Romantic irony introduced a potential

freedom for writers. They could momentarily escape the imposed frame of their narrative. Likewise in real life, one might escape the fictive story he repeatedly tells himself about the object of his desire. And who knows – if we censure ourselves now and then in the polis, we might retain our right to privacy and free speech.

The new songs here for male voice and piano are an inquiry into the limits of post-#MeToo Romantic irony. The variables are still the same: The subject is in danger of valorizing his desire precisely when he should sublimate it. He does not see clearly, and commits folly. Yet, some of this folly he welcomes – he does not want to see clearly. At what cost though?

A few words about the individual poems: The suitor in Shakespeare’s two sonnets is perpetually self-aware, a trait Harold Bloom identified in the Bard’s most famous characters. In Sonnet 147, the subject reasons about how he has lost his reason: “My reason, the physician to my love,/Angry that his prescriptions are not kept/Hath left me,

and I desperate now approve.” Even as he sees the folly of his desire, he chooses ruin. Here, self-ironizing doesn’t help, and leads to inertia: he perpetually diagnoses the problem yet never takes the bitter medicine.

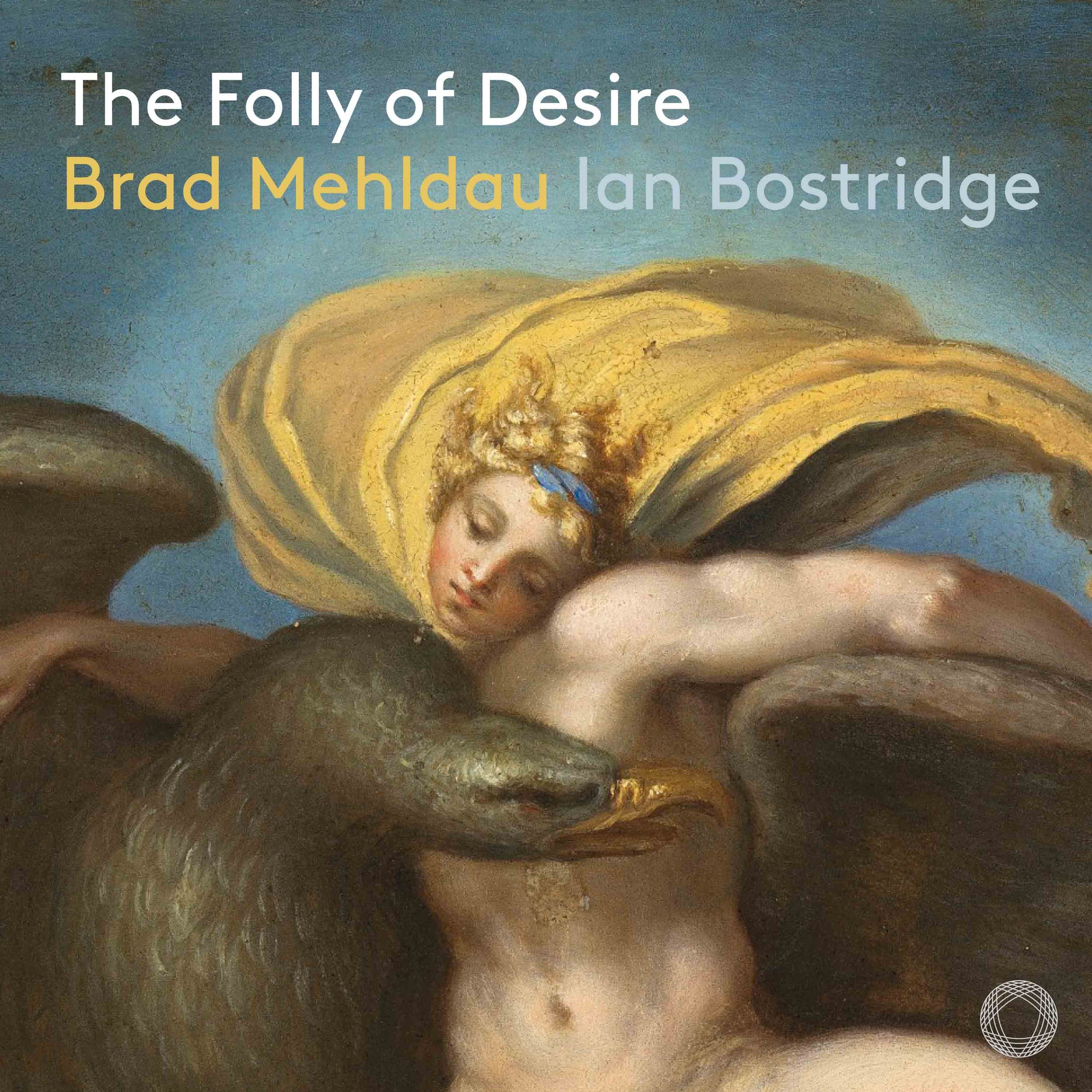

If tacit, genuine consent is the holy grail, then its most extreme, violent opposite is rape. Yeats’ mythological “Leda and the Swan” is unsettling because it locates a dark Sublime in Zeus’ brute overpowering of the girl, who, being so close the god, might have “put on his knowledge with his power.” In Brecht’s “Über die Verführung von Engeln” the dark humor from this master of satire has a purpose: Brecht describes the duplicity and self-sanctioning of the rapist-protagonist, who mockingly instructs the reader how to say or do whatever necessary to get what he wants. Here, the roles are reversed – whereas Zeus was the perpetrator, the angel here is the one perpetrated, a sublime figure whom one may not gaze at directly, even as he takes him by force – “Doch schau ihm nicht beim Ficken ins Gesicht”.

Goethe’s Ganymede craves the Father: “Aufwärts an deinen Busen, Alliebender Vater.” Zeus is less perpetrator and more pantheistic ideal – the divine expressed in eternal nature, into which Ganymede is received, ecstatically. This spiritualized Zeus is perhaps less Greek, but otherwise it was always difficult to believe that the youth would be so enchanted as he is lifted away – wouldn’t he be terrified, like Leda? Ganymede’s Liebeswonne (bliss of love) is intertwined his heilig Gefühl (holy feeling). They are both unendliche Schöne – eternally beautiful. The poem suggests that spiritual striving and earthly desire both seek the same thing: to cool our “burning thirst” – “Du kühlst den brennenden Durst meines Busens“.

What is the nature of that thirst – could lust then be a kind of holy impulse? Not if we understand the Holy to be benevolent. Desire in itself is blind by nature, never giving and always seeking to possess. We would hope that the Godhead would give us eyes to see our own folly. Yet such a sharp division between holy and carnal can itself become spiritual blindness. It becomes another strategy of denial and hidden complicity, of believing what you want to believe. What else were all those priests doing?

The unsettling suggestion in Auden’s “Ganymede” is that perpetration begets violence on the one perpetrated – which in turn might continue a cycle. For William Blake, lust and violence are destructive forces beyond our control, omnipresent elements that “shake the mountains”, as e.e. cummings proclaims in his raucous poem here, which yokes the two together more viscerally. The prelapsarian innocence is gone; Blake’s Rose is sick. Yeats calls on the holy sages to guide him in Sailing to Byzantium, for his heart is “sick with desire/And fastened to a dying animal/It knows not what it is.” Blake answers him from the past in Night II: Self-wisdom may be had, but “it is bought with the price/Of all that a man hath – his house, his wife, his children.” Both poets write of “Artifice” – be it deceitful in the case of Blake, or a property of eternity itself for Yeats. The burning thirst is unquenchable, be it of flesh or spirit, or finally, both.

– Brad Mehldau