Creativity in Beethoven and Coltrane

Installment 5 – Bird's Wide Wingspan

Harold Bloom’s idea of misreading celebrates originality yet gives a strong account of influence. It can be used to mediate between the competing tropes of rootedness and originality in the discourse on jazz, but only when considering a truly creative musician, as a truly creative musician is one who is simultaneously rooted in the past and expressing something new. Let’s consider John Coltrane as one such musician and apply the same three-period schema to him that we explored with Beethoven. His recorded output in the 1950s constitutes a roughly drawn first period. Two strong predecessors of his are Charlie Parker and Dexter Gordon, and Coltrane’s early style is a strong misreading of them both.

Dexter Gordon’s huge tone informs Coltrane’s tone. They both seem to always be blowing with all their might; there is a sentiment of abundance and generousness. But the musical choices Coltrane makes do not correspond to Gordon’s. Gordon favored singable phrases that were disarming in their simplicity and were rhythmically formatted smoothly and clearly to the chords he was blowing over. Here are the first 16 bars of his solo on “The End of a Love Affair”:

Dexter is a great place to start for beginning tenor players in the same way that Oscar Peterson is for piano players, because his lines are so clear. In the above example, we see quickly how he honed in on some of Charlie Parker’s bebop shapes. A large number of tenor players of his time, like Gene Ammons or Stanley Turrentine, share a quality of his: Bird’s phrases, rhythmically speaking, are often more square in Dexter’s reading then they would be in Bird’s own hands. They have a literal quality when we here them – they are telling us, “Here is how you connect the dots between this chord and the next chord.” This is not necessarily a criticism: players like Dexter or Gene Ammons used the tenor saxophone to propel the whole band with the rhythmic force of their phrases, particularly at a medium tempo, and the simplicity of the phrase had something to do with the force.

Still, looking at Dexter’s solo and then listening to Bird on any number of tunes with a similar chordal progression will highlight the revolutionary aspect of Bird’s style: Bird’s time is dead-on perfect, yet his phrasing is completely unfettered. His phrases start and end all over the place at different parts of the bar, and there is a far greater amount of rhythmic variety in his solos than is to be found in all of his predecessors. This is fitting. It is always the case that the inventor of a new means of expression has a seemingly unlimited reservoir of ideas; his followers, on the other hand, invariably take a piece of what he did and simplify it. With Bird, it is particularly easy to demonstrate this maxim, when we look at hard bop and everything that followed in his wake, right up until today.

Dexter’s phrases in the above example often start and end on eighth-note downbeats, like at bar 7, 13 and 15. As I’ll try to demonstrate later, this is actually unusual in modern jazz improvisation: Phrases tend to end on the up-beats. The repetitiveness of the descending II-V-I progressions in this tune throws the square quality of his phrasing style into relief. We could, if we wanted, take these phrases and shift their placement within the progressions like pre-made squares of lawn without any trouble at all. It wouldn’t change the essential character of the solo if we did this, moving chunks forward or backward:

Okay, maybe that last low F is a little weird! But you see what I mean. As great as Dexter’s solo is here – we wouldn’t want to change it of course – its phraseology is often generic; it is largely assembled from pre-made melodic shapes. The irony of Bird’s innovation is that, because of the clarity of his musical ideas, it was easy to snatch them and paste them, as licks, into a given chord schema. Playing Bird licks, verbatim, is one strong definition of jazz hell. Bird’s lines have an appealing symmetry that is easy enough to assimilate and mimic. Until Coltrane comes along, Bird himself is the leading transgressor from the normative path that he created.

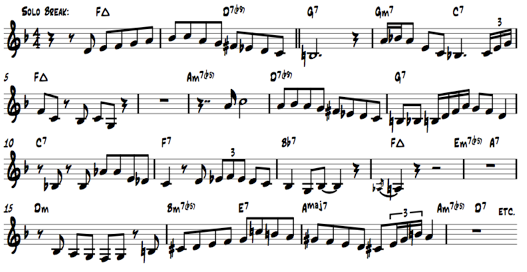

It would take a player like Coltrane to break free from this rhythmically formatted aspect of soloing, and if we look at the chronology of his stylistic development, we see that Coltrane’s first innovation was rhythmic – melodic and harmonic innovation came later. Here’s some of Coltrane’s solo on “If I Were a Bell,” with the Miles Davis Quintet in 1956. We start from the two-bar break after Miles’s solo; the top of the chorus is bar 3.

Because it’s in the same key as the “End of a Love Affair” example and also abundant in II-V progressions, we can see clearly where Coltrane comes out of Dexter and Bird, and where he’s starting to move away towards something rhythmically new and strange. In his solo break on the first two bars, the fluid stream of unbroken eighth notes could easily come from Dexter – not just the notes, but the rhythmic feel: slightly behind the beat, and more straight than dotted, wonderfully staggered. The phrase that follows, though, in bars 4 and 5, has more rhythmic variation and is broken up with rests. We see, importantly, triplets.

Bird’s solos were full of triplets that were interspersed between regular 8th notes; this feature of his solos gave them rhythmic variety. I’ll never forget a master class I attended years ago that the great jazz pianist and teacher Barry Harris was teaching. He was chiding all of us for playing endless chains of 8th notes. We may have absorbed some be-bop, but we weren’t dealing with triplets for the most part. We could have a little comfort in the fact that we weren’t alone – a lot of the great hard bop stylists from the 50’s onward didn’t really have triplets in their playing either. Having that in your playing, Harris maintained, was necessary for authentic bop expression – otherwise it was something else, something incomplete and weaker.

I never thought I was going to play be-bop like Barry Harris or another great Detroit pianist from the same generation, Tommy Flannagan, as much as I listened to them and absorbed their styles. But this idea that there was a true way of playing be-bop, and then there was this other way that did not make the grade – that made a great impression on me. To hear Barry Harris tell it, there were a bunch of players that I loved who did not make the grade.

To hear the alto saxophonist Lou Donaldson tell it – well, that was far more extreme! Lou would come down to a club where we younger musicians were playing and graciously listen to a set. And then when we’d hang out with him, he’d hold court. Boy, the things he would say! They often came in quotable sound bites:

“I got news for you – Coltrane killed jazz.”

Just when we’d be reeling from this – almost kind of getting dark because it just seemed so gloomy, what he was saying – he’d crack us up with some other acid remarks. For instance, his take on a band that was playing that week at Sweet Basil’s club, called The Leaders:

“The Leaders, huh?...I’d sure hate to see the followers!”

His appraisal of Ornette Coleman and much of so-called free jazz was equally devastating:

“Free jazz – yeah, that’s a good name for it. It should be for free! Nobody should pay to see that.”

What I discerned, listening to Barry Harris and Lou Donaldson, was that a strong paradigm led to the most rigid aesthetic. Once you found out how great something was, everything else would just keep falling away – you couldn’t use it anymore. It reminded me of Harold Bloom in his Shakespearean-scholar mode – even great writers like Melville, Joyce and the like, for Bloom, were just riffing on Shakespeare, and none of them matched his power. The way these guys loved Bird – and Bud Powell, as we’ll see in a minute – well, it didn’t leave room for much else. It made sense: The more you find out how great somebody is, the more you realized how his followers don’t match up to him. Still, it was troubling! Being young and hearing strong, unapologetic opinions from your elders is good tonic, though. After all, Barry Harris and Lou Donaldson were around when those giants were walking the earth. To them, Miles, Coltrane and Ornette were just guys like them – they were their contemporaries, and not the towering giants they are for younger generations. So those guys could get away with saying the kind of stuff Lou said. Nobody else – not a critic, not a younger musician – could. We’d just sound like clowns.

I always thought – jeez, if Lou thinks that about all those great players, what must he think of my little turd offering I just made that last set he heard? My mind reeled. It’s really, really good to be humbled like this, all the time. First as a young jazz musician, you should have that experience as you’re forming your sound. It’s like trimming off the fat from your style. It will make you less glib. It will make you less apt to spew and sputter and more apt to think before you express something. Then maybe you’ll think too much and you’ll get stuck in a rut of self-doubt…So be it – you go through that too, and get out on the other side with a stronger sense of your identity. Later, when you are at the height of your powers, at your full expressive reach, you should be knocked off your pedestal from time to time as well. Why? Not for the satisfaction of some boob who wants to tell you how and why you’re nothing. No one else can tell you that at any stage in your life as a musician. Only you can make those judgments about yourself; otherwise they don’t mean anything. If you’re able to make a judgment about yourself honestly, though, you can force a change; you can grow. And often the way to growth is realizing how limited you are, how little you have scratched the surface of someone else’s ouvre – someone like Bird, for instance. There are always opportunities, at every moment, for this kind of humbling cold shower.

The problem with teaching (and maybe the reason why I’m not convinced of my own ability to teach) is related to this. There is (not always but often) a frustrating Catch-22 with teaching: In order to be humbled – in order to be teachable – you have to comprehend the greatness of what towers over you, and if you really get that, doesn’t that comprehension at least imply that you know what to do already? So a teacher should teach humility – but that sounds so…pious. How does one teach that humility without being a jerk – the kind of old-fart teacher that everyone moans about because he or she just tells everybody how inconsequential and meager his or her playing is? It’s a fine line, and being able to walk that fine line is to me what good teaching is all about – nothing more, nothing less.

© Brad Mehldau, All Rights Reserved