Creativity in Beethoven and Coltrane

Installment 3 – Which Came First, The Melody or The Motif?

What is the theme, actually? This is a common semantic wrinkle in musical terminology. Specifically, is a theme simply the melody, or is it the melody and the harmony that underpins it? It would seem that the melody has primacy. The monophonic nature of a melody is a mnemonic aid – one internalizes that single line more readily than a group of simultaneous pitches. The melody rises to the forefront of one’s memory the way it rises to the forefront of much of Western music; it stands out in relief. One can recall a melody in a conversation with someone else, and say, “I love that piece that goes like that…” and then sing a snatch of the melody, obviously without accompaniment, since we usually don’t have a guitar, piano or string orchestra standing by when we’re on the go.

But many of us have probably experienced a particular phenomenon that demonstrates the varying degree of importance of melody in a given piece of music: Someone sings a melody to you, unaccompanied, asking if you know it – maybe he or she knows the music, but has forgotten the name. And you have no idea what he or she is singing – it does not register in your memory of all the music you know. Later that person remembers what the piece was and tells you, and of course you know it as well. Now, when the melody is sung again, you place the harmony under it in your imagination, and it all comes together.

Some themes, as great as they are, lean more on harmony than others and are very hard to sing to someone – and very hard to recognize only from the melody. Take for instance the riveting, bad-assed opening of Brahms’s First Symphony:

Many have remarked about Brahms’s First Symphony and its debt to Beethoven – the most overt example of that debt being the similar character of the theme of Brahms’ last movement and Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” theme in the finale of his Ninth Symphony. The opening of the Brahms above is a perfect example of one of those melodies that you cannot sing to a friend – it is pretty funny and frustrating to even try, and while Brahms also wrote many perfectly singable gorgeous melodies, this opening does bear out George Bernard Shaw’s quip, in this case at least, that you can’t sing Brahms. This disavowal of singability, I believe, is a Beethovenian gesture.

It’s easy to see how unsingable this opening is by trying to sing the violins or cellos, which double the melody in octaves. The upwards-chromatic climb of the line does not sound like much by itself. Then, starting at bar 5, the intervals grow and descend in wide leaps. Just to sing these intervals in tune requires pretty good pitch. This is not the melody that the layman walks out of the concert hall whistling or humming, like he does with a theme from a symphony of Tchaikovsky (who did not warm to Brahms’s music at all, at least in his correspondence).

The other factor is rhythmic displacement. Already in the first bar, Brahms introduces a key motivic component by making the C-sharp in the melody anticipate the downbeat of the following bar by one eighth note, and he continues with this practice, anticipating the downbeats at the beginning or halfway point of each bar. We shouldn’t underestimate the audacity of opening a symphony like this – if the symphony was hard enough to sing without a piano standing by, the anticipated upbeats ensure that your poor friend will be completely rhythmically lost as soon as you start singing it to him or her, unless you’re ready to bang out some eighth-note triplets. If Brahms was a less original composer, he might have written the opening without this rhythmic anticipation. Brahms was nothing if not a supremely imaginative rhythmicist. Here is how a more rhythmically “square” composer might have approached the opening:

The violins and cello now play on downbeats. It’s perfectly acceptable, but nowhere near as unsettling. The rhythmic displacement, along with the chromaticism and wide leaps of melody, is what makes the symphony unlike anything else. Everything works together: The rhythmic anticipation is easily felt and heard as a wonderful syncopation once we have the timpani, basses and contrabassoon pounding out those killer low C eighth-note pedal points. Likewise, the melody needs the rich harmony of the woodwinds, horns and violas that descend in the opposite direction to tell its chromatic story – and in this sense, then, the story is a harmonic story as much as it is a melodic story. That is big, and it’s why Brahms is so big: he was able to fundamentally shift the focus of musical narrative away from a singable melody. This, more than the cosmetic similarities between Brahms’ First and Beethoven’s Ninth, was how Brahms honored the symphonic legacy of his great predecessor.

The harmony itself is a kind of protagonist in Brahms’ symphony, and this is an undoubtedly modern gesture. Although the harmony of the opening is completely stamped with Brahms’ identity, he is not reinventing the wheel here – it owes much to Bach. (Play the opening of the symphony back to back with Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, for example.) Rather, Brahms’ innovation is in the way he reassign the role of a musical component like harmony in the unfolding symphonic narrative. This opening is undoubtedly about something, but it’s not something that you could pluck out and sing to a friend. Its identity is spread throughout the whole texture, and each part is interdependent. It is the malleability of identity that is deeply modern. To forsake melodic primacy is to forsake a definition of beauty that rests on clarity and comprehensibility. When the melody is not easily identifiable, what draws us in?

This rhetorical question is the subject of the symphony: As with Beethoven’s Ninth, the story begins with non-comprehending angst and moves towards the clarity of melodic primacy in the last movement. Both symphonies arrive at famously singable melodies in their last movements, implying a victory of melody over motif finally – a counter-disavowal of the more motivic form of expression that the symphonies began with. Beethoven and Brahms say to us, “Here is melody, it does indeed have primacy,” but it is really the motif that reigns supreme. What draws us in and holds us there for the duration with Beethoven and Brahms is the omnipresent motif.

For Brahms and Beethoven the symphonists, melody is a creation born of the motif – it is not the simple “gift” we talked about earlier: It must be earned. The motif is the source, the raw stuff from which melody springs. The melody acts like a mortal being: is always immediately perceivable yet intermittent – it comes and goes; it is always in flux, transient, and temporary. The motif acts like that mortal being’s omnipotent creator: it is not always immediately perceivable yet always present – it is constant and fixed; it is forever. The melody is beautiful; the motif is sublime. If the melodic activity throughout a large-scale work has motivic continuity, then it makes a claim at sublimity as well.

It’s easy to stumble on the term “motif” because it is vague: Often, the melody and motif are one and the same thing in a discussion about a work, but usually, the motif means an isolated part of the melody that has specific intervallic and rhythmic properties. It may sound melodic in itself; it may not. Here are the opening bars of Beethoven’s Ninth:

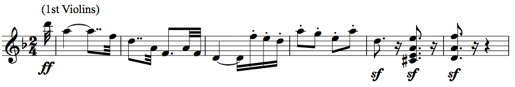

The motif has two quickly recognizable features: the interval of an open fifth, and the highly dotted rhythm that we hear first in the first violins, answered in the next bar by the violas and basses. As a melody, that figure is little more than a wisp. But that’s the idea. When a proper melody begins and we hear the first real theme of the movement at the pick up to the seventeenth bar,

we then see that the motif was preparing us for it – the melody employs the motif’s dotted rhythm, and the interval of the fifth is inverted.

For the first 16 bars of the symphony, Beethoven uses only two notes – an A and an E. Our ear, the first time we hear this, assumes that we are hearing a tonic fifth, with the A as the root. We sense that we are in some sort of “A” tonality. Whether it’s A major or A minor is not clear because there is no minor third or major third interval above the A that would indicate the mode. So we feel a sense of suspension, but whereas suspension in classical music from Bach on had implied an incipient resolution, here we are suspended in mid-air as it were, with no sign of where we might be headed. In those opening 16 bars, Beethoven has succinctly sketched a musical portrayal of chaos and formlessness.

For me, the effect of this opening never diminishes. Even though I know the symphony and know what’s coming, I am never prepared for the D-minor tonality that is coming down the pike, until it gets there and blasts itself into my body and brain. When the main theme does enter at bar 17, it creates a unique, unsettling feeling that was new to music: Instead of lessening the vertigo of the beginning, it increases it. It is as if we have been standing on a precipice in the clouds, not sure of what is underneath us. Then some of the clouds clear, we can see the ground from our high precipice, and all of the sudden we realize how far away we are from the ground.

But why are we still in the clouds, filled with only more vertigo? Why doesn’t the firm tonality of D-minor in the theme at bar 17 ground us? Hasn’t this whole beginning just been a long and drawn-out V – I progression? Not really: The open fifth of A and E, in itself, does not qualify as a functioning dominant: It lacks a C-sharp leading tone that would pull us towards the D tonic, or a G that would pull us towards the F natural of the D minor triad. It is stubbornly directionless. It is a motif, which means: It is an empty vessel for now, waiting to be filled. So when the D minor theme arrives, it does not feel like it resolves what preceded it – on the contrary, it feels like a usurping.

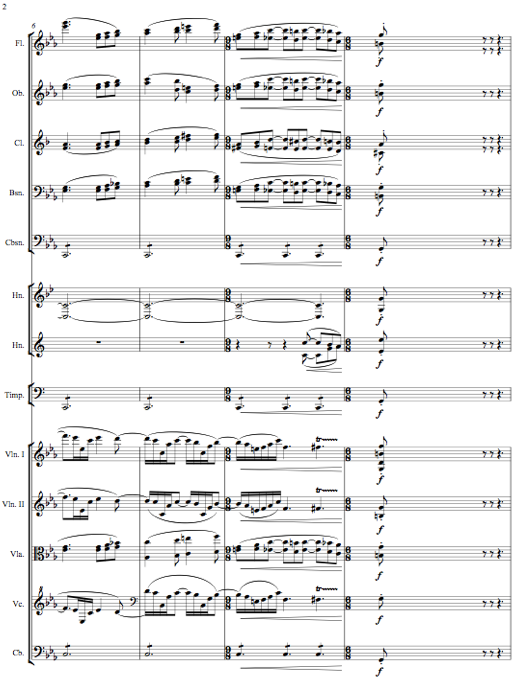

Beethoven creates that feeling of space between the dominant and tonic through the vagueness of the motivic open fifth. But how exactly does he draw those clouds away from underneath our precipice? The secret is the bassoons and the horns in B-flat. Let’s look at the full score from bar thirteen, as we head into that terrifying theme:

At bar 15, the bassoons and B flat horns play Ds. They do not start on the downbeat, but come in on the second eighth note of the bar. This is a masterstroke – they sneak in upon us rather than landing squarely, and in this way the effect is more of a subtle shift and less of an overt transition – an A pedal point is shifting to a D. After all – this is not any kind of harmonic resolution at all – it’s more like a drop. In a symphonic texture, everything always blurs together a bit, and Beethoven exploits this blur. We still have the motivic A-E open fifth in our ears and then the Ds of the horns and bassoons nestle under the A. For a strange, blurred moment at bar 15, our ears perceive something like this:

What is Beethoven up to here? He’s playing the same kind of game as he did in the Op. 96 quartet we looked at earlier: He is messing around with the hierarchy of the dominant and tonic, poking and prodding at the bedrock of Western tonality, this time by scrambling our ears right from the gate with this strange cipher of the open fifth that begins the symphony. Again, as in Op. 96, the tonic and dominant are in an adversarial relationship, repelling each other rather than attracting each other. And again, the bedrock relationship of dominant and tonic will become the main story of the piece.

Beethoven is like a storyteller who says to you: I am going to tell you about a beautiful princess and a prince and a dragon. And so you roll your eyes because you’re sure you’ve heard it before. And then he starts to tell you his tale. All the characters are there, and all of the themes are there – love, nobility, good conquering over evil, bravery – but some things have been switched around: The dragon, perhaps, is the one who falls in love with the princess. And the princess is torn between the dragon and the prince. Maybe the dragon isn’t purely evil; maybe the prince isn’t purely good…Maybe the dragon is the prince. Beethoven uses the same material as everyone else and then pokes a hole in it, so that something new springs forth and we see everything in a different way.

© Brad Mehldau, All Rights Reserved